Our History

A Foundation of Family: Lives of Legacy

L.W (Rudy) Moulder

A Life Remembered:

- 10/30/1903 to 12/12/1981

Founder & President

- 3/28/1946 to 3/2/1949

Truman Moulder

A Life Remembered:

- 5/2/1905 to 6/28/1994

President & General Manager

- 3/2/1949 to 12/30/1974

Dennis (Denny) Moulder

A Life Remembered:

- 5/9/1943 to 12/20/2009

President & General Manager

- 12/31/1974 to 12/20/2009

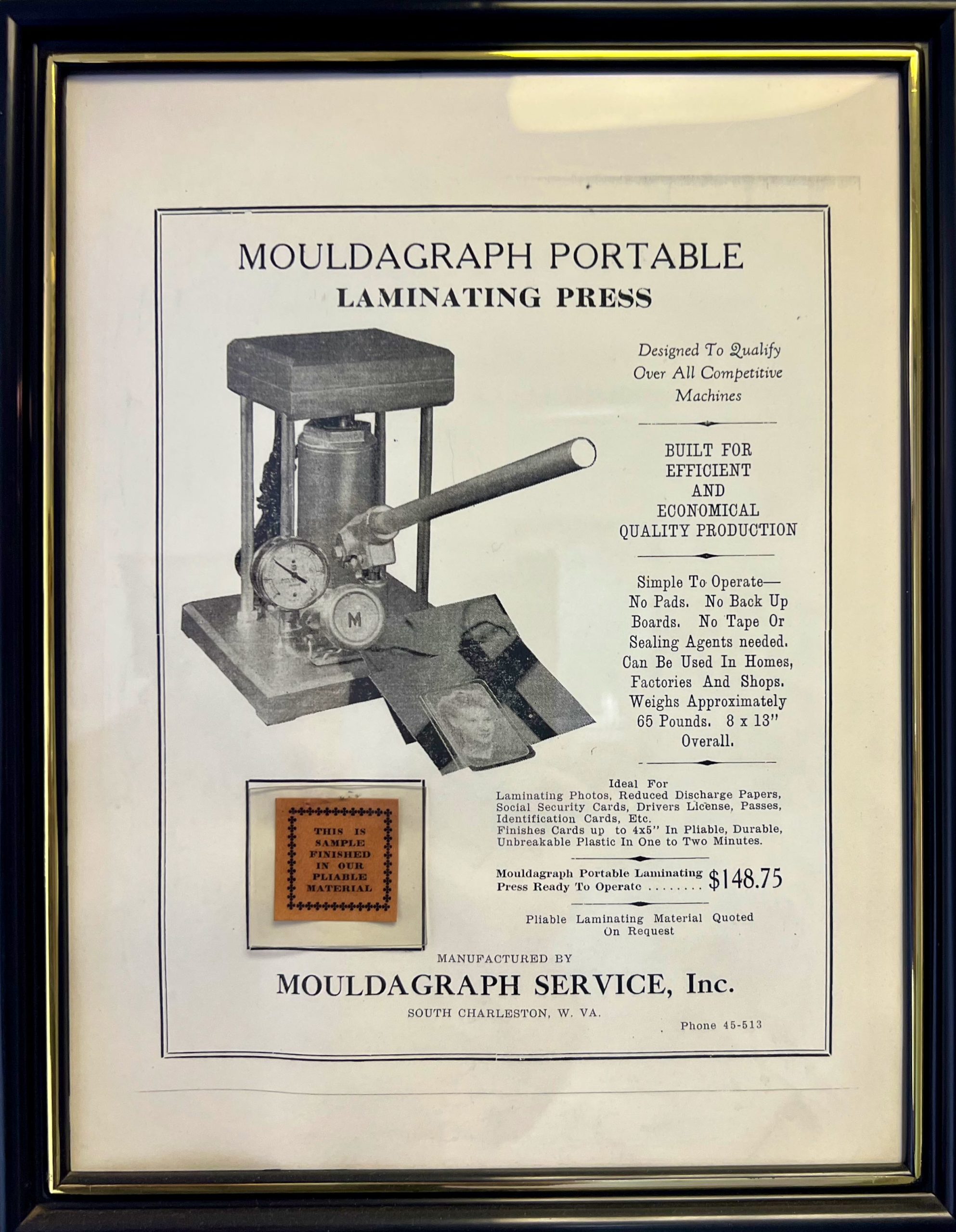

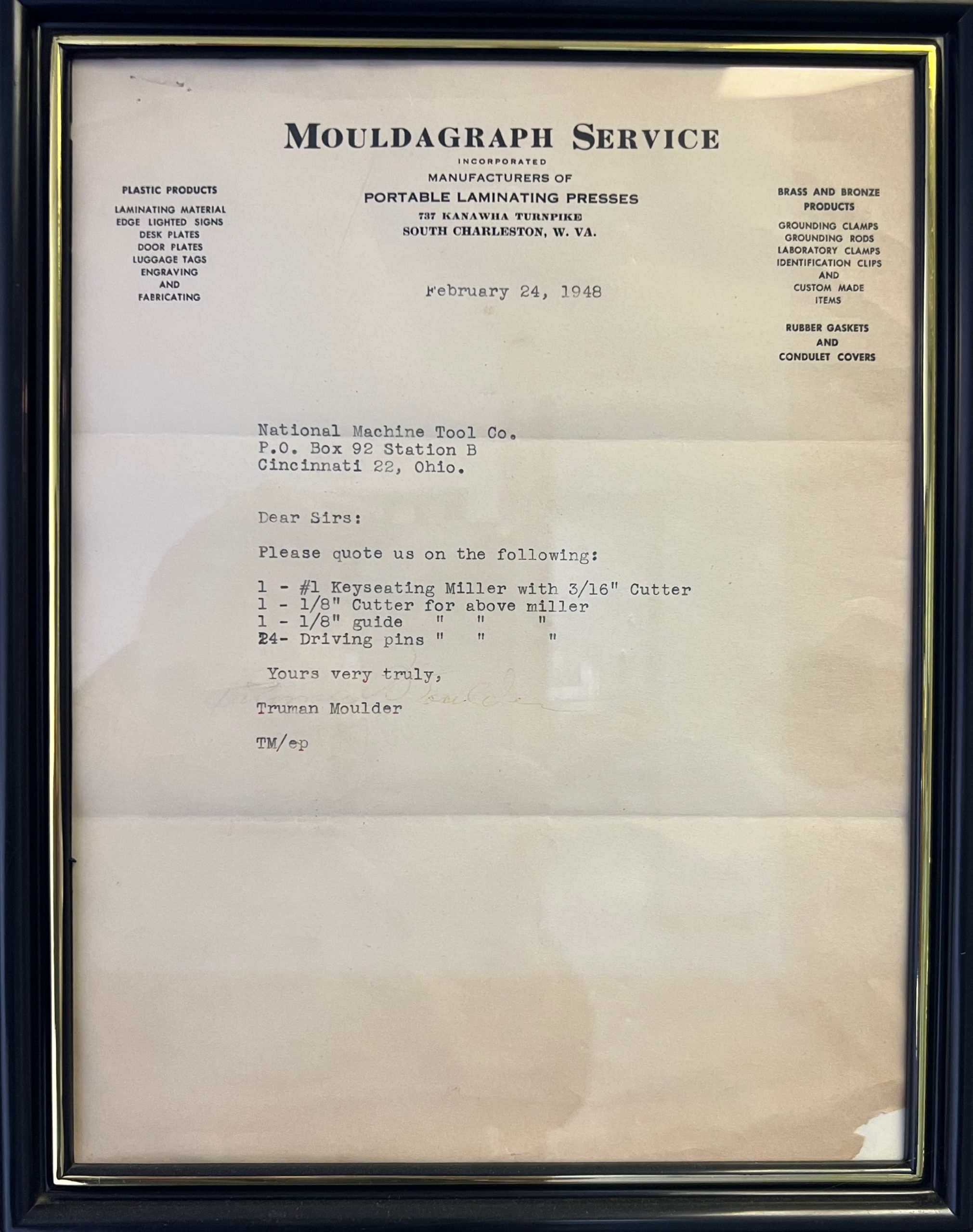

Founded as Mouldagraph Service Inc. on 3/28/1946, our name was changed to Mouldagraph Corporation on 4/13/1948.

In the News: Our History and Growth

Bursting at Its Seams

Versatility Guarantees Mouldagraph ‘s Present and Future

By Jim Balow, The Charleston Gazette

THE HALF-DOZEN or so excavator buckets in various stages of disrepair that sit behind the blue-and-white Mouldagraph Corp. building in Nitro signify the present for this business.

Inside, the computer numerical control (CNC for short) milling machines – each worth six figures – point to the future of the 58-year-old family-owned business.

“We are so versatile here,” said Dennis Moulder, the second-generation president and CEO. “We do a little bit of everything. We’re not dependent on any one phase.”

In today’s economy, that’s probably a good thing. Years ago, Mouldagraph’s relied heavily on the Kanawha Valley chemical industry. Most readers know what’s happened to that industry.

These days, with coal prices going through the roof, the company gets about 70 percent of its revenues by repairing coal equipment. Who knows how long that will last?

Once a technician in another room enters specifications into a laptop computer and forwards them by e-mail, the Korean machine churns out parts virtually by itself.

That’s why Moulder has been ploughing back many of the profits from the coal boom by investing in high-tech CNC milling machines.

“This is our future,” he told a pair of visitors on a recent tour of his shop, pointing to a HwaCheon vertical miller as big as a bedroom. “We spent $250,000 on this one.”

Moulder’s son Rudy, the field service manager and corporate secretary, said once a technician in another room enters specifications into a laptop computer and forwards them by email, the Korean machine churns out parts virtually by itself. “It’s the strongest vertical milling machine anywhere in the state,” he said.

In addition to milling parts to microscopic tolerances and repairing huge earth-moving machines, Mouldagraph fixes hydraulic machinery and distributes plastics.

“This kind of tells it all.” Moulder said, handing his visitors a company calendar that lists the variety of services he offers. “We’re like Wal-Mart.

What’s in a name?

Despite the corporate name, the company has little to do with molding or graphics. As you might have guessed by now, the name derives from the family name.

“It really started with my uncle, my dad’s brother, Lester,” Moulder said. “He was maintenance supervisor at [Union] Carbide. Everybody at Carbide knew him as Rudy.”

Moulder dug out an old poster of a desktop device, with a screw crank and pressure dial.

“It’s a laminating machine,” he said. “Lester was a genius. He could invent things. Carbide wanted to be able to laminate nametags so they would last. Rudy invented this machine in the basement of his house. Why he didn’t patent it. . . .”

L.W. “Rudy” Moulder combined part of his name with graph, which hinted at the nametags, and launched his business.

“We started out in plastics and move into machining. We were in South Charleston on Turnpike Road, the old Kanawha Turnpike. They took a house, gutted it and made a machine shop out of it.”

In 1947, Lester incorporated Mouldagraph and sold stock. When Carbide found out, company officials issued an ultimatum: Quit your day job or get rid of Mouldagraph. Lester sold his to Moulder’s father, Truman.

“In 1954, they came to Dunbar, built a building at Roxalana Road and what was then 10th Street. My dad, he managed that business until I took over in 1975.

“The principal business was working for chemical companies like Carbide and DuPont. It was job-shop-type work, like manufacturing shafts and bearing sleeves. Repairing pumps — we did a lot of that. They’d bring them in to us.

“Plastics was a sideline for us. We machined a lot of things out of plastic. Our main thing was desktops and floor mats. And Teflon; we make seals and gaskets.

“We’d go to banks and furnish the entire bank with chair mats [the plastic mats that allow desk chairs to slide around easily on carpeted floors]. We did all the chair mats in the new federal building.”

Eight years ago, despite adding a second building in Dunbar, the Moulders needed more space. They found it in a Nitro industrial park at the foot of the Interstate 64 exit ramp, across W.Va. 25 from the Pilot truck stop. They planned the move carefully, Dennis said.

“It took a year and a half to get it ready,” he said. “We’ve got a $2 million investment just in the building, buying the building and fixing it up to suit our needs. The electrical work was a lot of it.”

They built block walls to divide the formerly open space and installed overhead electrical conduits. Each bay houses its own department – plastics at one end, machining, welding, hydraulics and centrifuge repairs, coal bucket repairs in the rear.

Through all the moves and shifts in focus, the Moulders kept the old business name.

“We had a lady who called: “You do molding there, don’t you?’” said Dennis Moulder’s wife, Nancy, the vice president, head of human resources, office manager and safety director.

” ‘No.’ “Well, that’s false advertising.’ ‘No, that’s our name.’ ‘Oh.’”

All in the family

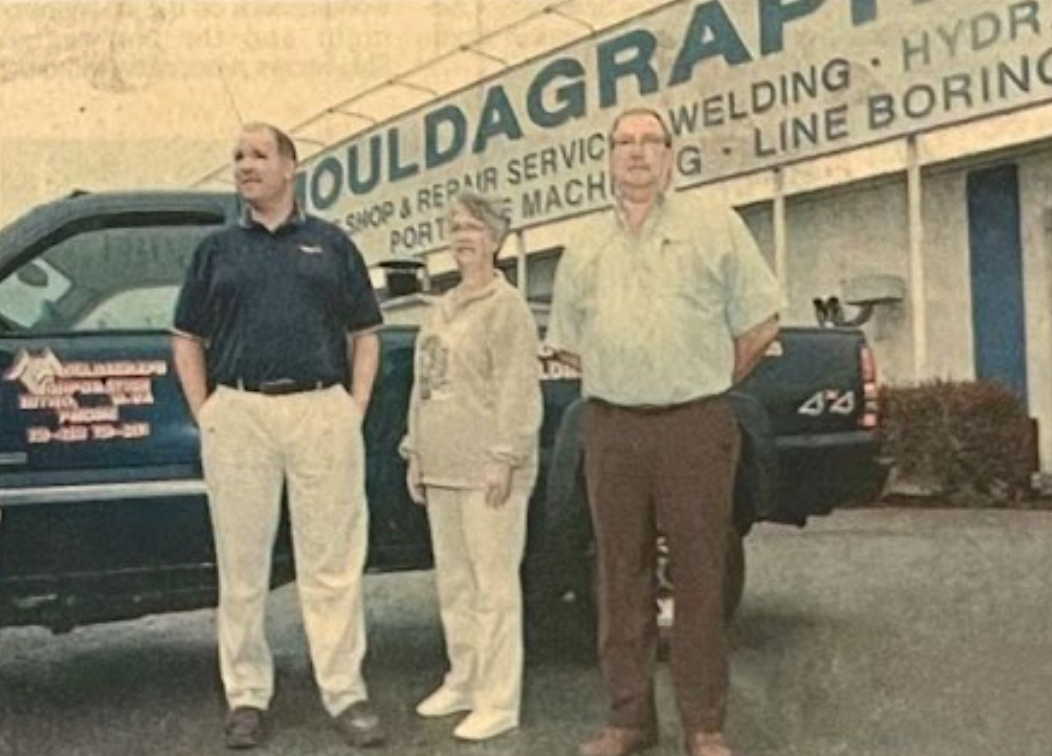

Dennis credits Rudy, 33, with the recent changes and growth in the company. He expects Rudy to take over the business when he retires in a few years.

A 1996 graduate of West Virginia University, Rudy has expanded the field service department and convinced coal operators to let him repair their buckets in the shop.

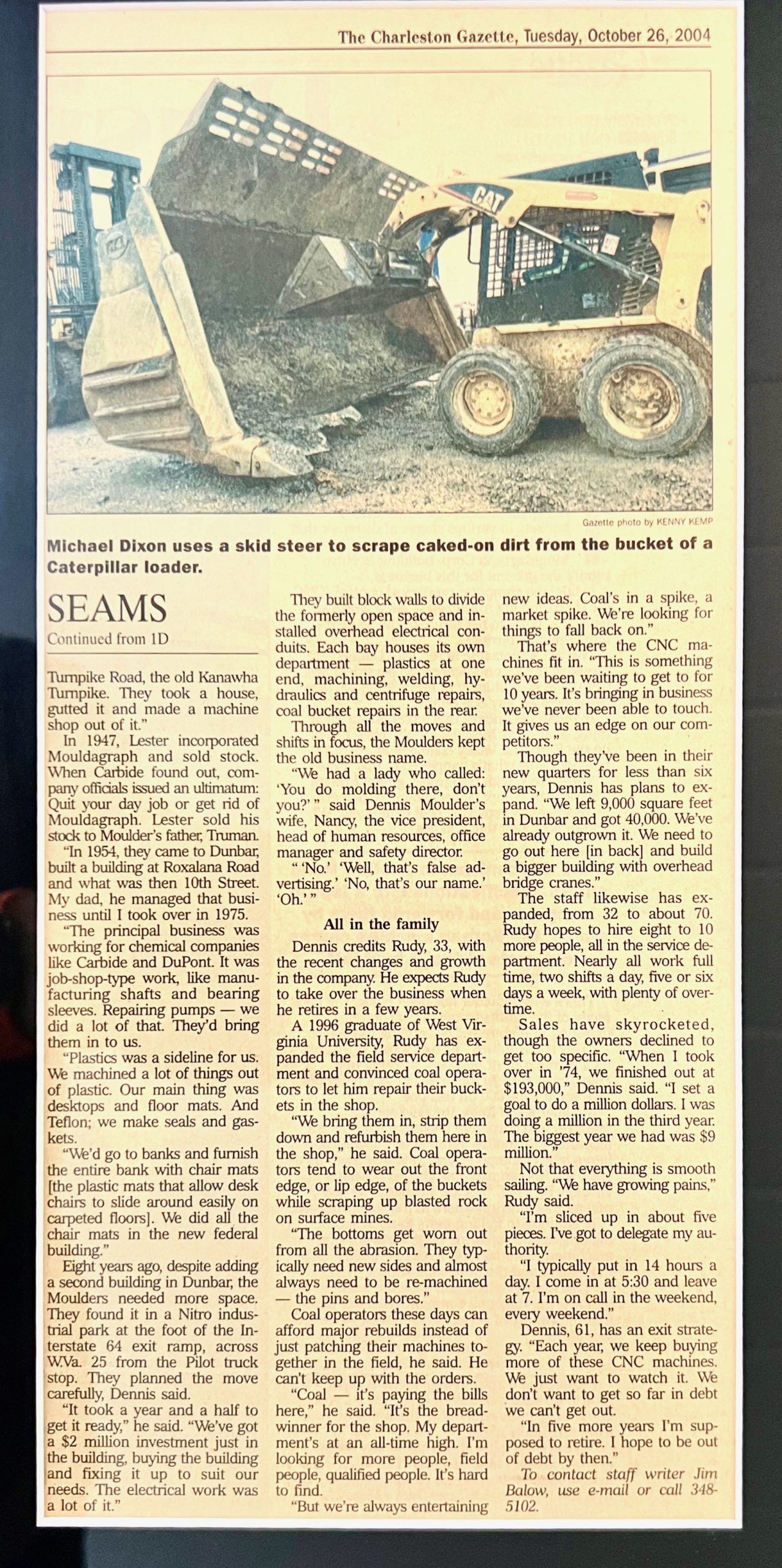

“We bring them in, strip them down and refurbish them here in the shop,” he said. Coal operators tend to wear out the front edge, or lip edge, of the buckets while scraping up blasted rock on surface mines.

“The bottoms get worn out from all the abrasion. They typically need new sides and almost always need to be re-machined — the pins and bores.”

Coal operators these days can afford major rebuilds instead of just patching their machines together in the field, he said. He can’t keep up with the orders.

“Coal — it’s paying the bills here,” he said. “It’s the breadwinner for the shop. My department’s at an all-time high. I’m looking for more people, field people, qualified people. It’s hard to find.

“But we’re always entertaining new ideas. Coal’s in a spike, a market spike. We’re looking for things to fall back on.”

That’s where the CNC machines fit in. “This is something we’ve been waiting to get to for 10 years. It’s bringing in business we’ve never been able to touch. It gives us an edge on our competitors.”

Though they’ve been in their new quarters for less than six years, Dennis has plans to expand. “We left 9,000 square feet in Dunbar and got 40,000. We’ve already outgrown it. We need to go out here [in back] and build a bigger building with overhead bridge cranes.”

The staff likewise has expanded, from 32 to about 70. Rudy hopes to hire eight to 10 more people, all in the service department. Nearly all work full time, two shifts a day, five or six days a week, with plenty of overtime.

Sales have skyrocketed, though the owners declined to get too specific. “When I took over in ’74, we finished out at $193,000,” Dennis said. “I set a goal to do a million dollars. I was doing a million in the third year. The biggest year we had was $9 million.”

Not that everything is smooth sailing. “We have growing pains,” Rudy said.

“I’m sliced up in about five pieces. I’ve got to delegate my authority.

“I typically put in 14 hours a day. I come in at 5:30 and leave at 7. I’m on call in the weekend, every weekend.”

Dennis, 61, has an exit strategy. “Each year, we keep buying more of these CNC machines. We just want to watch it. We don’t want to get so far in debt we can’t get out.

“In five more years I’m supposed to retire. I hope to be out of debt by then.”

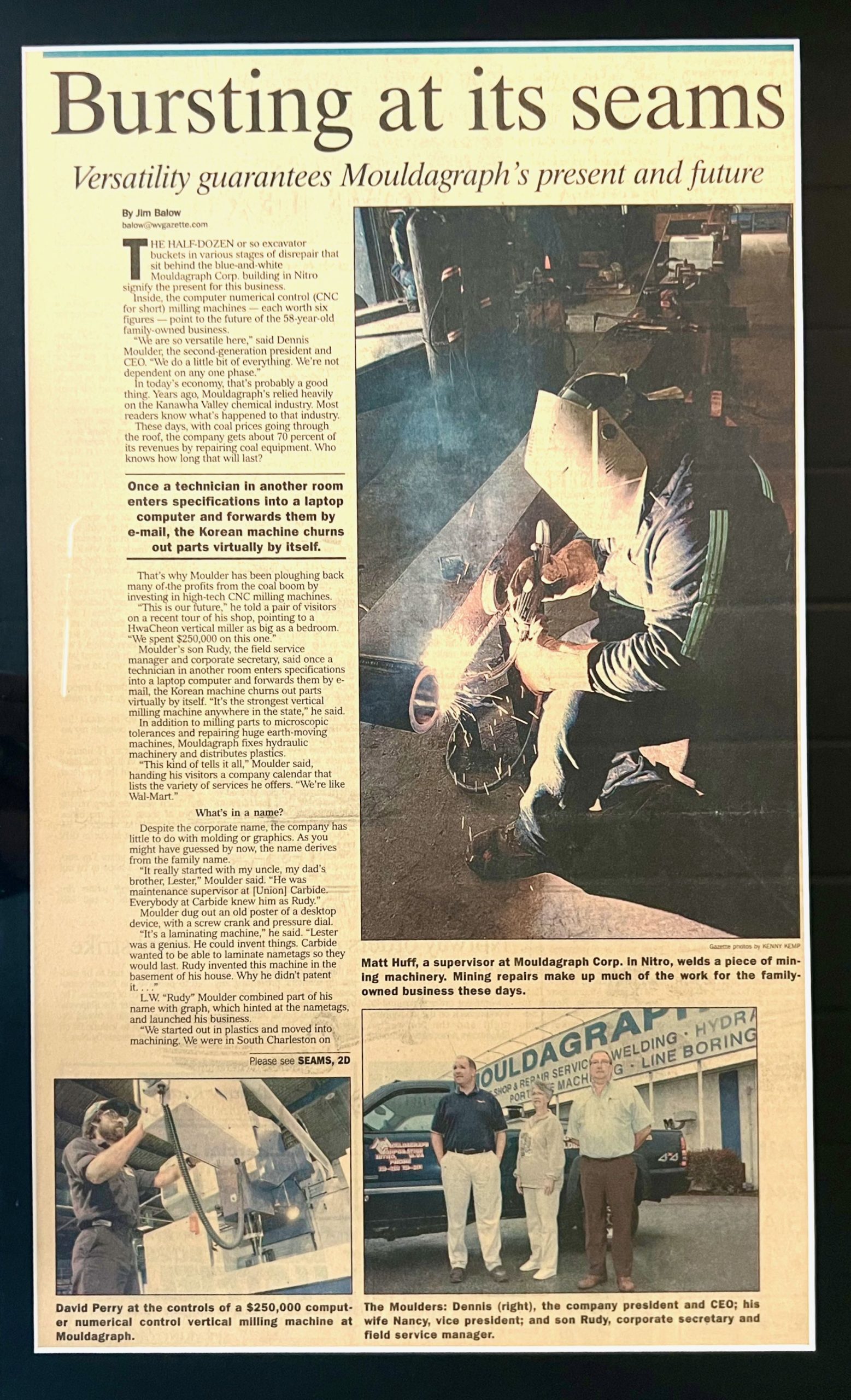

The Moulders: Dennis (right), the company president and CEO; his wife Nancy, vice president; and son Rudy, corporate secretary and field service manager.

David Perry at the controls of a $250,000 computer numerical control vertical milling machine at Mouldagraph.

Michael Dixon uses a skid steer to scrape caked-on dirt from the bucket of a Caterpillar loader.

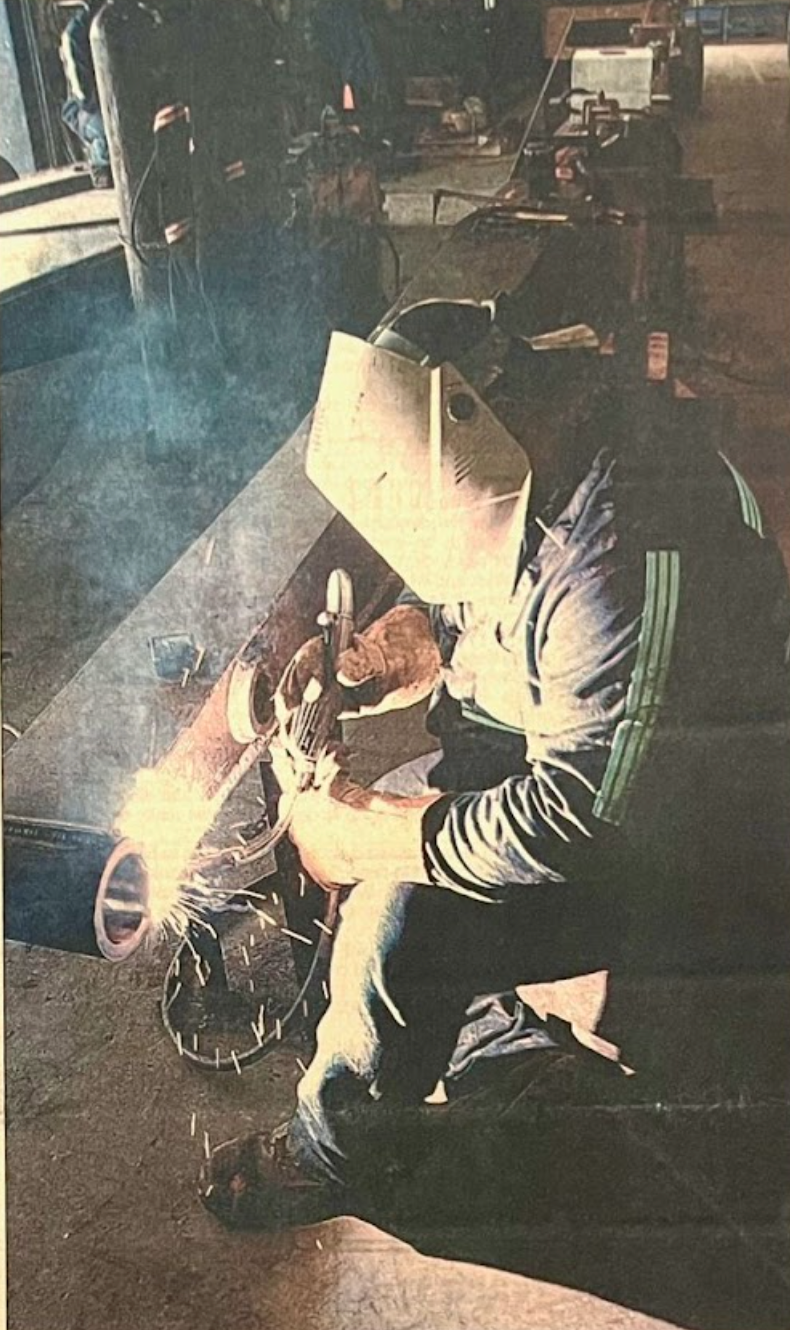

Matt Huff, a supervisor at Mouldagraph Corp. In Nitro, welds a piece of mining machinery. Mining repairs make up much of the work for the family-owned business these days.

Our Early Facilities

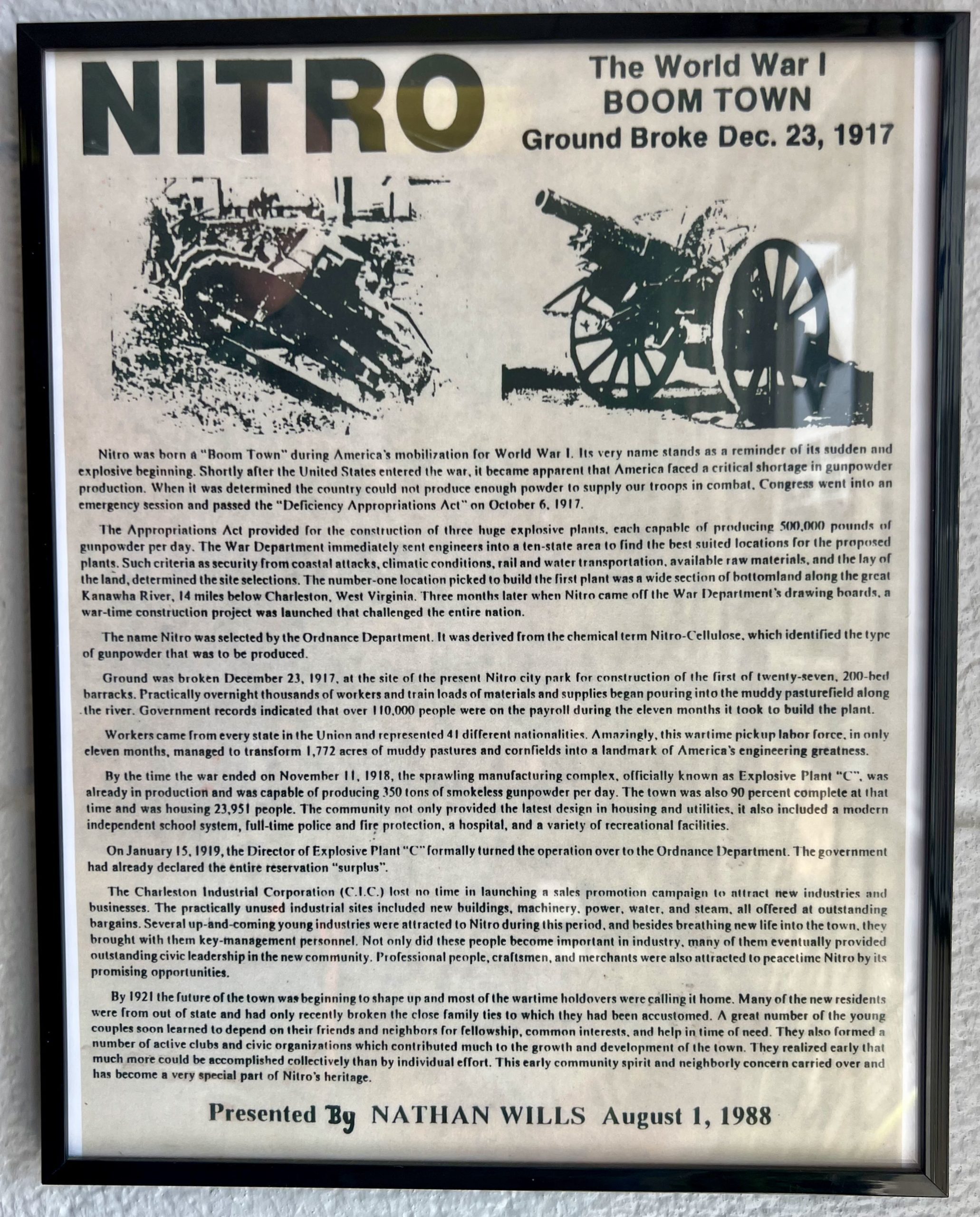

The Amazing History of Nitro, West Virginia

NITRO

The World War I BOOM TOWN

Ground Broke Dec. 23, 1917

Nitro was born a “Boom Town” during America’s mobilization for World War I. Its very name stands as a reminder of its sudden and explosive beginning. Shortly after the United States entered the war, it became apparent that America faced a critical shortage in gunpowder production. When it was determined the country could not produce enough powder to supply our troops in combat. Congress went into an emergency session and passed the “Deficiency Appropriations Act ” on October 6, 1917.

The Appropriations Act provided for the construction of three huge explosive plants, each capable of producing 500,000 pounds of gunpowder per day. The War Department immediately sent engineers into a ten-state area to find the best suited locations for the proposed plants. Such criteria as security from coastal attacks, climatic conditions, rail and water transportation, available raw materials, and the lay of the land, determined the site selections. The number-one location picked to build the first plant was a wide section of bottomland along the great Kanawha River, 14 miles below Charleston, West Virginia. Three months later when Nitro came off the War Department’s drawing boards, a war-time construction project was launched that challenged the entire nation.

The name Nitro was selected by the Ordnance Department. It was derived from the chemical term Nitro-Cellulose, which identified the type of gunpowder that was to be produced.

Ground was broken December 23, 1917, at the site of the present Nitro city park for construction or the first of twenty-seven, 200-bed barracks. Practically overnight thousands of workers and train loads of materials and supplies began pouring into the muddy pasture field along the river. Government records indicated that over 110,000 people were on the payroll during the eleven months it took to build the plant.

Workers came from every state in the Union and represented 41 different nationalities. Amazingly, this wartime pickup labor force, in only eleven months, managed to transform 1,772 acres of muddy pastures and cornfields into a landmark of America’s engineering greatness.

By the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, the sprawling manufacturing complex, officially known as Explosive Plant “C”, was already in production and was capable of producing 350 tons of smokeless gunpowder per day. The town was also 90 percent complete at that time and was housing 23,951 people. The community not only provided the latest design in housing and utilities, it also included a modern independent school system, full-time police and fire protection, a hospital, and a variety of recreational facilities.

On January 15, 1919, the Director or Explosive Plant “C” formally turned the operation over to the Ordnance Department. The government had already declared the entire reservation “surplus”.

The Charleston Industrial Corporation (C.I.C.) lost no time in launching a sales promotion campaign to attract new industries and businesses. The practically unused industrial sites included new buildings, machinery, power, water, and steam, all offered at outstanding bargains. Several up-and-coming young industries were attracted to Nitro during this period, and besides breathing new life into the town, they brought with them key-management personnel. Not only did these people become important in industry, many of them eventually provided outstanding civic leadership in the new community. Professional people, craftsmen, and merchants were also attracted to peacetime Nitro by its promising opportunities.

By 1921 the future of the town was beginning to shape up and most of the wartime holdovers were calling it home. Many of the new residents were from out of state and had only recently broken the close family ties to which they had been accustomed. A great number of the young couples soon learned to depend on their friends and neighbors for fellowship, common interests, and help in time of need. They also formed a number of active clubs and civic organizations which contributed much to the growth and development of the town. They realized early that much more could be accomplished collectively than by individual effort. This early community spirit and neighborly concern carried over and has become a very special part of Nitro’s heritage.

Presented By NATHAN WILLS

August 1, 1988